(C) 2013 Gonçalo M. Rosa. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC-BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

For reference, use of the paginated PDF or printed version of this article is recommended.

Reports of amphibians exploiting subterranean habitats are common, with salamanders being the most frequent and studied inhabitants. Anurans can occasionally be observed in caves and other subterranean habitats, but in contrast to salamanders, breeding had never been reported in a cave or similar subterranean habitat in Western Europe. Based on observations during visits to a drainage gallery in Serra da Estrela, Portugal, from May 2010 to December 2012, here we document: (i) first report of Rana iberica reproduction in cave-like habitat, representing the fourth report of an anuran for the Palearctic ecozone; (ii) oophagic habits of the tadpoles of Rana iberica; and (iii) Salamandra salamandra predation on Rana iberica larvae. These observations, particularly of Rana iberica, highlight our lack of knowledge of subterranean ecosystems in the Iberian Peninsula.

Subterranean habitats, amphibians, anuran reproduction, larval predation, oophagy

Caves and other subterranean habitats contain a biodiversity that has long intrigued biologists, such as Darwin and Lamarck (

In the Palearctic region, amphibians are relatively common in subterranean habitats; however only one species is obligate cavernicola (Proteus anguinus Laurenti, 1768). Other salamanders are known to use caves during part of their life cycles (e.g., Paradactylodon persicus (Eiselt & Steiner, 1970), Speleomantes spp. Dubois, 1984, Chioglossa lusitanica Bocage, 1864 and Salamandra salamandra (Linnaeus, 1758) (

Worldwide, breeding by anurans in subterranean habitats has only been confirmed for three additional species of leptodactylid frogs in the Neotropic ecozone: two of genus Eleutherodactylus Duméril and Bibron, 1841 inhabiting Caribbean islands (

The Iberian brown frog (Rana iberica Boulenger, 1879) is endemic to Portugal and north-western and central Spain. Although it is a typical mountain species, this frog can be common in coastal areas at low altitude. The species inhabits streams with cold and clear waters, rocky substrates, and abundant vegetation surrounding the margins (

Predators of Rana iberica have been documented across all life stages. Adults are prey of water snakes (Natrix maura (Linnaeus, 1758) and Natrix natrix (Linnaeus, 1758)), Vipera seoanei Lataste, 1879, small carnivores such as Neovison vison (Schreber, 1777), Genetta genetta (Linnaeus, 1758) and Lutra lutra (Linnaeus, 1758) (

Here, we report for the first time evidence of Rana iberica reproduction in a subterranean habitat, the fourth record of an anuran for the Palearctic ecozone. Furthermore, we discuss the natural history of Rana iberica, including the report of a new predator of larvae and oophagic habits of its tadpoles.

Serra da Estrela Natural Park is located in north-central Portugal (40°20'N, 7°35'W) and is the largest protected area with approximately 89000 hectares (Fig. 1). It is one of the highest mountains (1993 m a.s.l. at Torre Plateau) in the Iberian Sistema Central. The climate is temperate-Mediterranean with Atlantic influences, presenting dry and warm summers and a wet season from October to May with frequent snowfall at higher altitudes (

Because of its geographic location, topographic and climatic conditions, Serra da Estrela has several ecosystems that are unique in Portugal. In addition, this area contains many rare and endemic species. This region is one of the most biodiverse in Portugal and is considered an Iberian Peninsula biodiversity hotspot (

Serra da Estrela Natural Park and hypogean habitat used by individuals of Rana iberica: A entrance of the underground spring B Schistostega pennata covering walls and floor of the drainage gallery C horizontal tunnel of drainage gallery. Photo A by Madeira M, B by Rosa GM, C by Laurentino T.

Several drainage galleries were created for water capture in the 1950s, even before the establishment of the boundaries of the Natural Park. Galleries are characterized by a horizontal tunnel that penetrates the side of a hill. Typically, galleries are of limited width (ca. 1 m) and height (1.5 m), and extending several meters into the hillside (Fig. 1A–C; see also

During an initial visit to one drainage gallery (40°20'36.95"N, 7°42'50.23"W, 985 m a.s.l.; Fig. 1) near Sazes da Beira (Seia) gallery in May 2010, several (not quantified) Rana iberica were observed within this subterranean habitat. This particular gallery extended 25 m with walls, as well as some patches of the floor, partially covered by goblin’s gold (Schistostega pennata (Hedw.) Web. & Mohr) (Fig. 1B). It has a door that is partially closed (with no light penetrating beyond about 5 m, when the door is opened), providing a true dark zone to this habitat. In addition, a small, shallow stream (average of 5 cm water depth) with low flow ran the length of the gallery. Water pH of 7.1 measured on 24 April 2011.

The unusual sighting of Rana iberica motivated a series of subsequent visits that started in 2011: every three months until November 2011 and monthly between December 2011 and December 2012 to understand the use of this artificial subterranean habitat by this species. We obtained data on the activity cycle and reproductive period of Rana iberica by noting first the presence of individuals inside the gallery, secondary sexual characters (nuptial pads in males) and breeding behaviour (individuals in amplexus), and the presence and developmental stage of larvae. Based on previous data (

All life stages were observed in the gallery during the study period, particularly adults, which were observed every month of the year (Table 1; Fig. 2–4). Adults were observed active both during the day and night often standing on the ground or in crevices (Fig. 3B), swimming underwater or floating, seeking refuge in holes or even climbing up the walls (Fig. 3C) (inactivity being defined by lethargy, habitually observed in hibernating frogs outside the gallery, found hidden under rocks during winter months). Individuals were mainly found beyond the first 5 m from the entrance, where the most intense daylight penetrates. These individuals often presented the lichen-shaped spots on their backs that are typical of this region (Fig. 3A;

Polar coordinates representing the activity cycle and breeding period of Rana iberica in two different sites (inside the drainage gallery in Sazes and the whole area of Planalto Superior) in Serra da Estrela; Portugal. Dark brown areas: post-metamorphic phase; beige areas: larval phase; green areas: adults in breeding activity.

Adult individuals of Rana iberica found inhabiting a drainage gallery in Serra da Estrela, Portugal: A male with typical lichen-shaped pattern on the back B female hidden in a crevice of the gallery C male climbing up the wall D couple in axillary amplexus in water E axillary amplexus out of the water. Photos by Rosa GM.

Absolute number of Rana iberica individuals (post-metamorphics or larvae) and clutches of eggs found per visit (month) inside a drainage gallery at Serra da Estrela Natural Park, Portugal. In some months data is restricted to detected (+) and not detected (-).

| Year | Month | Post-metamorphics | Larvae | Clutches of eggs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Juveniles | ||||

| 2010 | May | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2011 | May | + | + | + | + | + |

| August | 9 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| November | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| December | + | + | - | - | - | |

| 2012 | January | 7 | 6 | 0 | 31 | 6 |

| February | + | + | + | + | + | |

| March | 6 | 4 | 0 | 64 | 4 | |

| April | 8 | 4 | 0 | 52 | 2 | |

| May | 7 | 3 | 4 | 71 | 1 | |

| June | 6 | 4 | 6 | 12 | 0 | |

| July | + | + | + | + | - | |

| August | 8 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 0 | |

| September | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | |

| October | + | + | + | - | - | |

| November | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| December | + | + | + | - | - | |

In both years of this study, the breeding season occurred between December and April (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, the little available data on the activity of Rana iberica in Serra da Estrela is confined to the higher elevations (Planalto Superior, area above 1400 m and up to the summit). Although the gallery studied is located about 400 m below this limit, we noticed obvious differences in the activity patterns of these populations (Fig. 2). Because of very low temperatures, individuals seem to hibernate or reduce activity between December and February in the Planalto Superior population. Additionally,

Adults were found frequently in mating attempts and in amplexus. Occasionally, more than one male was seen trying to mate with a female, which has also been reported by

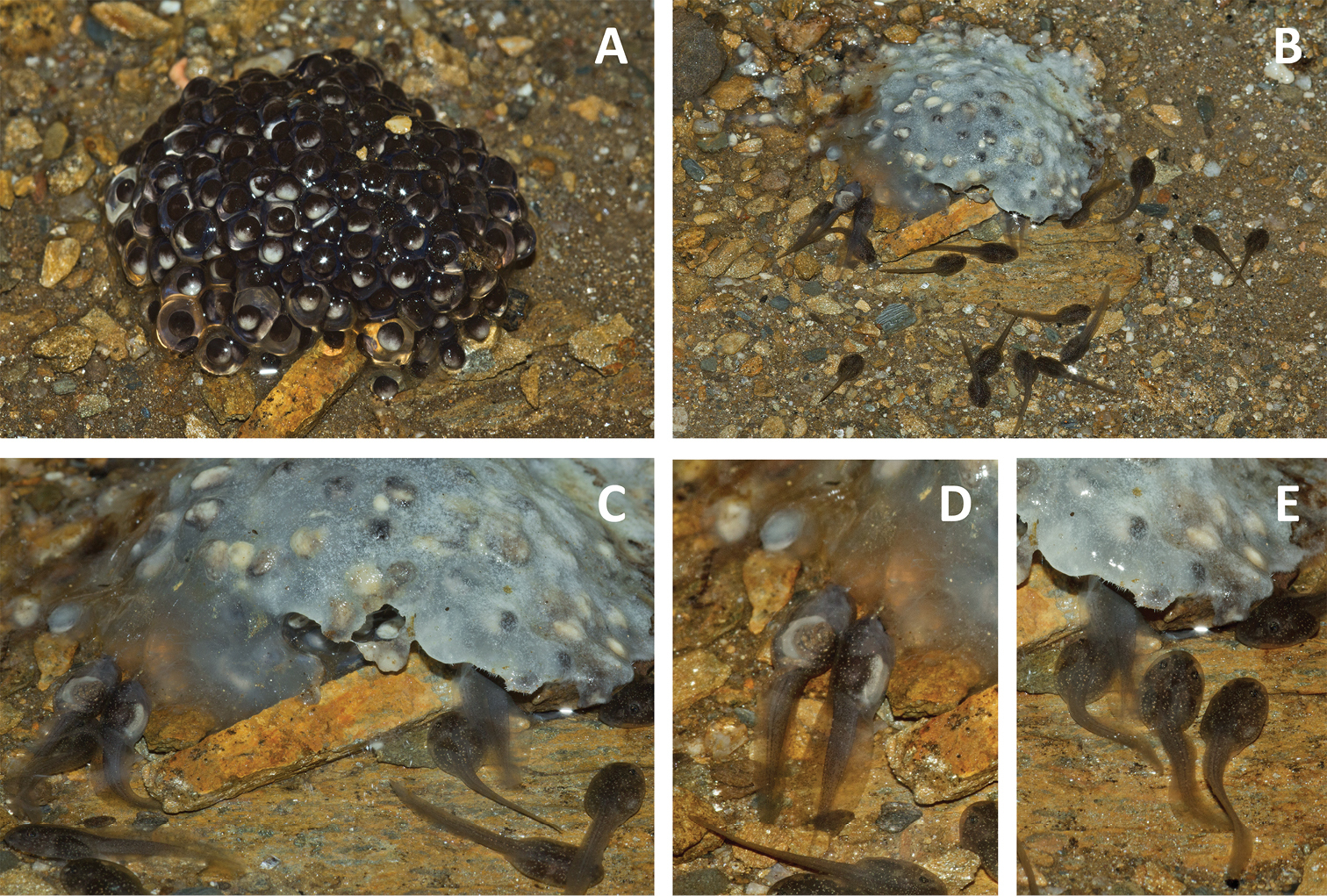

Clumps of eggs with a gelatinous coat were generally laid and stuck to submerged rocks in the stream (except for one case: see Fig. 5A and description below) and recently hatched tadpoles could be observed stationary above the egg mass for about two weeks (Fig. 4A–B). Tadpoles were pale grey in coloration and became darker during the second week (Fig. 4C;

Egg and early life stages of Rana iberica inhabiting a drainage gallery in Serra da Estrela, Portugal: A egg mass stuck to underwater rock (28 January, 2012) B eggs’ detail with new born tadpoles (one day old) C tadpole with dark pigmented colouration (Gosner stage 25; 11 March, 2012) D recently post-metamorphic individual (31 May, 2012). Photos by Rosa GM.

Oophagy was observed in this subterranean population of Rana iberica. A clutch of eggs was probably laid in water, but got stranded when the water level presumably dropped. When we first noticed, the mass was already > 90% above the water surface (Fig. 5A), preventing normal development of the eggs. This situation turned the egg mass into a source of nutrients for free swimming tadpoles (at least three weeks old) from other clutches. Several tadpoles were observed feeding on the eggs (Fig. 5B–E), a behaviour also reported for the first time for this species. Conspecific oophagy is a form of cannibalism (

Rana iberica tadpoles feeding on lost clutch: A fresh egg mass of Rana iberica laid (mostly) above water surface (11 March, 2012) B group of tadpoles feeding on the dead eggs (29 April, 2012) C, D and E close ups of tadpole feasting on the eggs. Photos by Rosa GM.

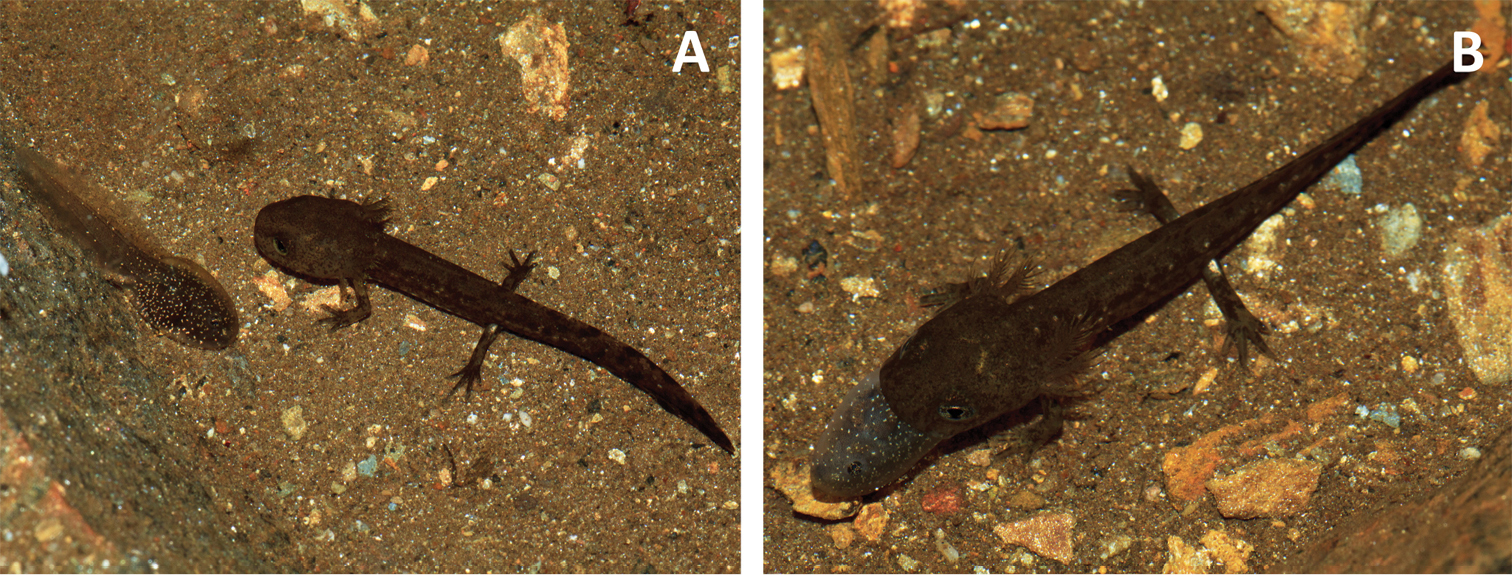

The gallery is also inhabited by other amphibians, including female Salamandra salamandra gallaica that use the underground spring to give birth to small larvae. During one visit to the gallery on the 29 April 2012, two predation events were recorded. Two Salamandra salamandra gallaica larvae (post stage 46;

Salamandra salamandra gallaica larvae predation upon Rana iberica tadpole on the 29 April (2012): A individual of salamander approaching tadpole instants before seizing it B salamander larval ingesting tadpole. Photos by Rosa GM.

Anurans from the genus Rana appear to be the most common anuran visitors of caves and similar subterranean habitats, both in the Nearctic and the Palearctic regions (

Additionally, few other questions have been raised: is the presence of the species in the hypogean habitat temporal and accidental, or permanent? Does this apply to the entire population or only a part of it? Is the hypogean population in contact with the nearby epygean ones, and if so, where and when? A mark-recapture study (possibly by taking advantage of the characteristic dorsal pigment pattern of adult frogs) might help to shed some light on these questions, providing a better insight into the dynamics of this interesting population.

The Mediterranean region has experienced dramatic shifts in climate in the past (

We are grateful to Raoul Manenti, Truong Nguyen and Thomas Ziegler for the bibliographic support. A special thanks for everyone who supported the field study, particularly José Conde, Madalena Madeira, Telma Laurentino, Marta Sampaio and Diogo Veríssimo. Pedro Moreira for the insight about the frogs’ activity. Jessica J. Scriven for the comments before submission. Finally, we are very grateful to both reviewers (Sebastiano Salvidio and anonymous) for their useful comments that significantly improved the manuscript.